- Home

- Marcy Gordon

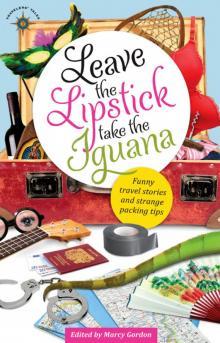

Leave the Lipstick, Take the Iguana Page 7

Leave the Lipstick, Take the Iguana Read online

Page 7

In no time, I deemed myself and demanded others call me “Motorcycle Mama.” Unfortunately, my title came crashing down quickly. The faux-wood heel of my right boot fell off among the rotten fruit in the plum orchards and I was forced to walk like a carousel horse, slowing maneuvering up and down; faster if I was excited.

My friend Kristin didn’t care about my lack of proper footwear and was a loyal passenger, clutching my abdomen as I pushed the throttle as far as it would go. We’d dig out empty plastic water bottles from the recycling bin, unscrew the caps, and hold them open in the wind, trying to catch cicadas. We’d fill the under seat compartment with freshly picked raspberries, park the machine, then devour the slightly-smelling-like-gasoline-exhaust fruit.

After I turned sixteen, the cherry bomb Kawasaki could no longer fulfill my desires to explore the world. It wasn’t as cool as a vehicle that required an actual drivers license. I retired the machine to my father’s stone quarry, to be used as a courtesy vehicle.

I never looked back. Wasn’t that what my ATV taught me—to look onward. To see what was ahead, under the overgrown grass. To see if this journey had any visible speed bumps?

Then, almost twenty-four hours after we said “I do,” my husband and I landed on a 100-step cement staircase in Santorini, Greece, where tan men wearing white linen uniforms and white-framed sunglasses painted our hotel’s already-white exterior bright white.

“Are your legs shaking,” I asked Oscar when we finally arrived in our cave-like suite appropriate for all types of romantic encounters. My thighs felt like jelly. “I mean, I’m a certified pilates instructor. I’m in shape. The best shape of my life.” I caressed my rear end, as if to say, look, this thing is rock hard.

“It’s just these stairs … they’re so steep and there’s so many,” I continued.

As we dipped zucchini fritters in tzatziki under the umbrellas on the beach, the faint noise of ATV engines roared in the background. I half expected to hear crashing plates and the guttural “OPA,” so I was slightly disappointed and ignored the revving of motors.

As we ate sticky Greek donuts on the side of a cobblestone street, I rolled my eyes at the tourists flying by on four-wheelers smaller than my seven-year-old nephew’s.

It seemed like everywhere we turned, the island was infiltrated with these multi-colored ATVs.

“They look like idiots, in their helmets and the big RENT ME sticker plastered on the side of their new toys,” I said to Oscar about the tourists flying by. “They are screaming ignorant vacationer. No Greek people ride those things.”

“Actually, I think it’s pretty cool,” he said. The romantic honeymoon soundtrack playing in my mind stopped. “When else would you be able to ride one of those on city streets? And it’ll certainly help with all of the stair climbing. You’re always complaining about your burning thighs. I think we should do it.”

Deep down, this was exactly what I was afraid of. Oscar, who grew up in Venezuela, had a very different upbringing than I did. While I was riding my go-carts and helping my dad dig dirt on an excavator, he was learning how to program a computer to say “hello.” I had gotten the crazy ATV riding out of my system early on.

“Well, my body can handle the stairs,” I said. “I don’t want to rent one and look stupid.”

“I do.”

Perhaps it was the fact that we had just said those words so lovingly to each other in front of our friends and family. Perhaps it was something inside of me that wanted him to have that feeling I had as a kid. That feeling of being free, of having the wind blow through your hair at excessive speeds.

Whatever it was, I caved and we soon found ourselves at the rental shop, forking over Oscar’s New York license. The Greek sales associate was stereotypically blasé, and I couldn’t help but check my sunburn in the reflection of his Raybans.

Five minutes later, we strapped on bright orange salad-bowl-style helmets and were out the door. The gas tank was on empty (which I felt to be a bad omen), so we stopped at a gas station. Oscar had no shame as he pumped fuel into our ride. He smiled, giddy with excitement, and proudly wore his helmet into the building to pay. I stared down, diverting eye contact with the drivers waiting behind us. When was it socially acceptable to take this treacherous looking helmet off?

Once refueled, Oscar pushed the 100-horsepower engine as far as it could go. It wasn’t nearly as fast as my Kawasaki, and oftentimes we had to wave of our arms, without turning around, for cars to pass us. Going downhill, we both leaned forward, hunched over, to make sure we were as aerodynamic as possible. But it didn’t make a difference. This thing was slow.

Within an hour, we found ourselves at the top of a mountain, looking down on the classically beautiful white buildings. I forgot I was wearing a helmet and attempted to kiss Oscar, only to have my visor poke his eye. After a quick check to make sure his eyeball was still intact, that free feeling came back to me.

I turned to Oscar and whispered, “I’m your Motorcycle Mama now.”

Leigh Nannini lives in the Hudson Valley region of New York where she works at the family business, a stone quarry. Similarities between the Nannini family, a stone quarry. Similarities between her life and that of Pebbles Flintstone are abundant. Despite her resistance, Leigh still finds herself in the passenger’s seat of various forms of tourist-only transportation: camels in Giza, cable cars in Hong Kong, and tuk-tuks in Bangkok. She comes to terms with this.

NICO CRISAFULLI

An Indian Wedding Nothing Like the Movies

The honor of your presence is requested at the Whisky A Go-Go.

I’ll be the first to admit, my perceptions of traditional Indian weddings came mostly by way of movies I’d seen. And in these movies there were always scenes of wonder, glittering nose rings, austere ceremony, even the goddamn Holy Fire ritual. I figured my first Indian wedding would have whooping from the multitudes, all peacocking around in perfect Bollywood cinematography. There would be monkeys in hats, a fish on a tray, and young couples that barely knew each other.

Sadly, my first Indian wedding had none of these things. Mine was what you might call a catastrophe. Mine saw me sitting in a grim little circle of teenage boys, cutting plastic cups of cheap whiskey with water from a pipe sticking out of a bare concrete embankment.

It was Varanasi in Spring. And like some do, I’d signed up for a sunrise boat ride down the Ganges. Varanasi. A city whose river is far holier than your city’s river and doesn’t even care, a city whose skyline looked like Shiva’s baby boy had spilled its bag of toy blocks all over the landscape and left them there for a thousand years. It was a destination I’d been greatly looking forward to, perhaps for no other reason than to see what all the fuss was about, to peer into the arcane depths of the Mother Ganges and feel the mystical covenant that keeps Indians coming in droves to wash and immerse themselves in water that with one sip might kill any single one of them. I wanted to make sure those amoebic currents had a level of sanctity to negate the painfully scientific facts I knew about it—the jets of human sewage that gutted into the water just upstream from where the masses dunked their heads, prayed to Shiva, and felt shivers of his spirit enter their bodies. I’d heard of its fecal count, and it wasn’t good. On the river, I could see how that foul effluence tainted its water jet black, see the detritus of a million purges, but I was sure I could overlook all that if I just squinted hard enough.

There were four other people who signed up for the tour that morning along with me, all of whom were no less than fifteen minutes late in coming down. Needless to say, my blood boiled. I wanted them hurt. I wanted to wave my itinerary in their faces and tell them this was my sunrise morning and not to fuck it up! But as is the irony of angry men, the world’s ill manners embarrassed me with kindness. I was sitting with the young tour leader, Ravi, at a hard plastic table on the guesthouse patio, fantastically groggy, but excited about the idea of seeing some of the world’s most pristine activity from the comfort of a painfully adorable

wooden boat. Through the pre-dawn hum, I heard Ravi engaging me with small talk.

“Many pilgrims are coming here to bathe in the Ganga. It is a very pious river.”

“Yes,” I said. “I’m looking forward to the sunrise.”

“You know,” he said quite matter-of-factly, “tonight I am being married.”

“How’s that?”

“Today is my wedding day.”

“Er, you … Are you serious?” I croaked, stopping short of asking just what he was thinking working on his wedding day. Instead he read the incredulousness on my face and offered his open palm as evidence. It was decorated to the wrist with the swirling henna curlicues indicative to, sure enough, an Indian wedding. I almost cried.

That night he was to marry his bride, and the most wonderful day in his life started with me, a jaded American forty-something who hadn’t washed his underwear in a week. I wanted to hug him.

Things changed quickly when I realized he was asking if I would please do him the honor of joining him that night at the wedding. And would eight o’clock be okay?

I stiffened with panic.

Tonight? Me? Who was I even? I had nothing to wear! Certainly no English would be spoken. But most importantly, what would I wear? My formal attire at that point of my travels consisted of exactly one pair of long pants and one shirt with a collar, and those were, shall we say, vastly unbefitting of a fine occasion. I was sure there was a giant curry stain on the thigh and who knew how much cow shit my butt had been privy to over the previous weeks. Screw it, I thought. I’d be going to that wedding, cow shit and curry notwithstanding.

That night, I made it back to the guesthouse at exactly ten minutes to eight. Six minutes to shower and four-and-a-half minutes to deal with the pant leg, and I was out the door. Only to find myself waiting over an hour in the guesthouse kitchen with nothing to do but stand around with two of Ravi’s young friends, Manu and Prem, steamrolled by an encouragingly offered and unceremoniously quaffed bottle Officer’s Choice whiskey.

It was approaching 9:30 when we finally and for no evident reason left that drinky kitchen. The boys moved me quickly out of the guesthouse and through the narrow alleys with their arms woven through mine, whisking me away to an event utterly unsuited to my rapid descent into intoxication.

Very soon thereafter I was being placed at a feast. Roughly 150 wedding guests were gathered together eating, barely speaking, hungry teeth devouring a seemingly endless supply of food. Through no fault of my own I was stuffed full of India’s finest fare: poori, naan, samosas, spoonfuls of saag, ladles of dahl—dinner I would’ve loved to enjoy had I not been a tipsy and altogether inappropriate mess. I’d wanted just one damn moment to enjoy a plate before another load of fluffy bread and chickpeas was placed before me. It seemed the boys were intent on making me puke. They dropped dish after dish on the table, only to take them away half-eaten, and replaced with another even more exotic and unidentifiable serving.

By this time the three boys around me had turned into six, all grinning the most impish Indian grins, impossibly white teeth shining at me, giggling as they stuffed me like a prized turkey.

Somehow the dining portion revolved to a close. But before I could say “so where’s the happy couple,” I was being led again by the elbows out of the banquet area, the two previous armholders now a half-dozen hands on my shoulders and back, tittering loudly, scurrying me toward a shadowy section of ghats fifty meters away, down twenty steps toward the murky waterline, a hundred nautical miles from my comfort zone. Manu and Prem, who had recently vanished, returned with another bottle of Officer’s Choice whiskey. Thin plastic cups were distributed to each of our now group of seven, which at my initial refusal, and their subsequent insistence, were filled deep.

Back in the kitchen we were cutting our whiskey with splashes of Limca soda. There on the ghat there was no Limca, only a thin line of water trickling out of a pipe sticking brazenly out of the concrete. The kids were busy cutting their own cups with the pipewater, mine following soon after. Was it even potable? I couldn’t say. The rust told me otherwise but it didn’t seem to matter to them in the slightest.

They cheerfully diluted my hard alcohol with pipewater that likely proffered a hundred billion harbingers of toilet Hell. I was at a loss. My drunkard’s decision however was to drink it down and pray to the Lord God to assist in any future bathroom duties.

The night completely bypassed the dancing, bypassed the revelry and the tossing of marigold petals—in other words, bypassed all the fun. Gone was any donning of saffron turbans and the carrying of fish on silver trays. What happed next was the blatant dismissal of everything I had up until that moment expected from an Indian wedding, because Manu, the unmistakable alpha dog of our little group, decided that my now prodigious levels of intoxication were better suited to my guesthouse bedroom than the wedding—it was his fault!—and he ordered me taken home.

My supplications to speak with the groom were heard however and I was led back into the wedding party fray. There was a beehive of activity orbiting the bride and groom, a zoo of fawning and petting and flashbulb-sparkling cholis. Through a tilting haze I zeroed in on Ravi. He looked weary but fine in a perfectly pressed, richly embroidered wedding sherwani, standing next to what I assumed to be a flange of family members. I elbowed my way to him.

I remember quite the opposite of lucidly bowing my head, squashing my palms together and gushing Namastes and thank yous and I’m totally honored to be heres to any and every nearby wedding party member, effectively bullet-holing the room’s sing song Hindi with a tawdry American obsequiousness. I also hardly remember my other embarrassing attempts at chivalry (did I really kiss the hand of the bride? Did I do that?). I soon noticed Manu approaching, parting the ocean of awkwardness.

Like a dog urging its master to take it outside, Manu’s hand gently pressed at my elbow. The pressing soon became a pulling, but not before I felt it a good idea to wrap my arms around the mother of the bride in a boozy embrace, whereupon the pulling became a desperate yank punctuated with a solid, “We go now, Baba!”

Later, as the whisky curtain rose to illuminate the evening’s events, I considered my night. I thought of how its moments played out like the images on a Bollywood screen, but nothing at all like the movies, my own sequel to someone else’s lucky day. And Varanasi to me would be defined by it, not the by the mystical ceremonies executed under bedazzled skies, but by the bottoms of alcohol cups as they shaped the very memories I would eventually come to laugh at. It wasn’t my idea of a holy wedding in a spiritual city, but it would have to do. It was all I had.

Nico’s perspective of the world all but reversed upon visiting India for the first time in 2011, his respect for cows, spicy chai, and modern plumbing suddenly elevated. He now lives with his wife and young son along the shores of the San Francisco Bay, but promises an imminent return to India.

CHRISTINA AMMON

Ciao Bella

The ying-yang of adoration: damned if you do and damned if you don’t.

When my mother turned fifty, we decided it was time she traveled. Aside from a few quick trips over the Mexican border, she’d never left the United States. She wanted to go some place clean—yet lively, cultural—but not overly foreign. We decided on Italy.

Only one thing worried her. Watch out for the men, a few people warned. They are aggressive, will grope you, and make lewd comments—ESPECIALLY since you are blondes. Italian men love blondes.

At fifty, my mom was quite good-looking and walking down the street together we accrued roughly about the same amount of male attention. She had a nice figure, beautiful face, and stylish clothes. I was less kempt, but at twenty-four had sea-white hair that flowed all the way down to my waist.

We brainstormed. What could we do to fend off the unwanted advances? Tying up our hair or hiding it beneath a hat was an option, but seemed too oppressive. So instead, we prepared what we would say in response and honed our snide looks. If an Italian m

an approached us with a dramatic proclamation of love, we knew exactly what we’d say: I like your approach, now let’s see your departure.

Or were he to say something like I know how to please a woman, we would say, Then please leave us alone.

And reserved for the lewdest offenders: Sorry, we don’t date outside our species.

Mom decided that instead of hotels, we would stay in the convents with the Holy Sisters—far, far away from the machismo of Italy’s streets. We would be fine.

Should we bring pepper spray? My mother fretted. I laughed, but she was serious.

We started our tour of Italy in Venice, riding gondolas down the waterways and wandering the cobblestone streets. We were so awed by the beauty of the city that we forgot all about the perils of Italian men. We were too busy dining on pasta e fagioli, drinking the house wine, and blowing cigarette smoke over our shoulders. We spent a morning loitering in the Piazza San Marco where I fed what seemed like a thousand pigeons. One late afternoon, we strolled under the lines of clean laundry fluttering in the Venetian breeze.

Florence was next and we loved the bridges, walking the length of Ponte Vecchio back and forth a dozen times. We toured Galleria dell’ Academia, eyeing the perfection of Michelangelo’s David, and almost blushing at his beauty. So far, all was going well. Days had gone by, and not a single Italian man had leered. We hadn’t even heard a Ciao bella! Mom began to relax.

Days peeled away in Lucca next. Each morning we rented bicycles and rode around the wall surrounding the town. We spent days drinking cappuccino and looking at clothing and ceramics. On Mom’s birthday, I decorated her bike in crepe paper and loaded the basket with cakes and presents. We rode around the wall, parked our bikes, and celebrated at a picnic table. Happy fiftieth Mom, I said, lighting the candles.

On the way to Rome we put our guards back up. Rome would be the surely be the epicenter of unwanted catcalls and groping. We set stern expressions, ready to admonish any Georgio or Piero who got out of line.

Leave the Lipstick, Take the Iguana

Leave the Lipstick, Take the Iguana