- Home

- Marcy Gordon

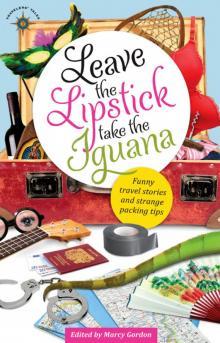

Leave the Lipstick, Take the Iguana Page 5

Leave the Lipstick, Take the Iguana Read online

Page 5

I was picked up from my hostel and met a few of the other tourists who would be joining me: a Brazilian who was only on a day trip (what a weakling), an Argentinian couple who were doing an overnight trip (hmmm) and two Swedish guys who were doing a four-day trip (wait a minute). That was the first “oh, shit” moment: when I realized that I was the only person signed up for five days. Why was it that everyone else, including the hard-core backpackers like myself, was willing to skip out early?

This became a little clearer when we arrived at the floating lodge. It was modest: a green building, indeed floating, anchored in place with ropes tied to the huge trees that lined the river. No electricity, simple accommodations, excellent for my spiritual return to nature. Our guide, Joshua, sat down with us at a wooden table that immediately reminded me of Girl Scout Day Camp, from when I was about the age of seven, and started going over how long everyone would be staying. One day, two days, four days … “And who signed up for the jungle survivor trip?” He asked. No one answered. He checked his list again. “It says it’s an american ….” All eyes went to me.

“Excuse me?” I said.

“I have you down here for the survivor trip. Five days, right?”

I searched my memory. What had the guy from the travel agency called my trip? Had he used the word “survivor” in his description? He couldn’t have, there was no way I would have been stupid enough to sign up for a “survivor tour” … or did I? I couldn’t remember the exact words, it had been so hot in that office and I had been so thirsty. I mustered some kind of incomprehensible squeak, which Joshua interpreted as an affirmative response. “O.K. then! Let’s go piranha fishing.”

The afternoon was pleasant: piranha fishing was interesting enough, although I was reprimanded by Joshua several times for not concentrating and failing to pay enough attention to my fishing line, as the piranhas stole all my bait and evaded my hook. I eventually managed to catch two, at which point I immediately began to feel bad for the piranhas and remembered that I hated fishing. Minus one point for my return to nature.

We returned to the lodge for a fish dinner with spaghetti (funny how fish and spaghetti seemed to be considered complementary menu items in Brazil), and then went on a nighttime tour of the river. The scenery was, indeed, beautiful. The water in the smaller tributaries was still, and in the dark, it looked like a black mirror reflecting the stars and shoreline. We were surrounded by silence, except for the stir of the wind on the leaves and the hiss of insects.

I, however, was preoccupied for the duration of the nighttime tour: I was trying to scheme up a good excuse to leave after Day 4, when the Swedish tourists were also leaving. Bum foot? (I did have an impressive-looking ankle brace and ace bandage with me from an injury, and an authentic limp.) Family emergency? No good, how would I have found out about a family emergency in the middle of the Amazon without internet or electricity? Fear of the jungle? No, I had more pride than that. Vague and embarrassing woman disease? Not to be ruled out.

I was only distracted from my brainstorming when Joshua docked the boat in a dark, swampy area surrounded by trees almost entirely submerged in water. Since it was the rainy season, the water was high: it was like being in a flood zone, with fully-formed tree trunks and branches at eye level. Joshua jumped out of the boat. “O.K.,” he said with thickly accented English, “I go catch alligator. Wait here.”

As the five of us exchanged looks (“Wait, did he just say he’s going to bring back an alligator?”), he shouted back, “And no talking!”

O.K. No talking. We waited in the boat, all of us painfully aware of the extremely hard wooden benches uncomfortably digging into our asses. I dozed off for a bit. It was a little eerie, this swamp. Pitch black dark, except for Joshua’s flashlight bobbing in the distance as he swam and waded through the trees. Vines hanging down, one of which I was carefully leaning away from because there was a spider hanging on it. After an eternity of forty minutes, Joshua returned: in one hand, he held a forked stick with a snake tied to it; in the other, a baby alligator. Holy shit.

“O.K., O.K.! This snake kill many people every year. So no touch head of snake. You want to hold?”

Fuck no, I don’t want to hold! And if it kills many people every year, why the fuck are you waving it around the inside of this boat? I heard Joachim, one of the Swedes, murmur from the back of the boat, “Was this included in the waiver?” Waiver, I thought frantically, did I sign a waiver? Or, more importantly, did they ask me about any health concerns or problems I might have? Does this boat even have a first-aid kit?

“Joshua,” I said, throwing tact to the wind, “are the guides here trained in first aid?”

“Why you worry? Everything fine. Someone get bit, I give them jungle medicine.”

Oh, excellent. If I get bit by a deadly poisonous snake, a man wearing a bright orange Speedo swimsuit will give me jungle medicine.

Now, as a newbie to the jungle, I learned a very important lesson that night. The best way to survive in the jungle is through a careful combination of alcohol and pharmaceuticals. I was only foolish enough to spend one sober night in the jungle: the first one. I spent the night tossing and turning in my room, sweating from the heat and waking up every half hour to spray more DEET on my skin and wishing I had gone for the 100 percent. At this point, I didn’t care if I had mutant children because of the carcinogens in my insect repellent: I just wanted these monster-mosquitoes to leave me alone. After that first restless night, I embraced the philosophies of all our guides, who (while they claimed to love nature and their jobs) drank their weight in alcohol on a nightly basis. And it made sense: who wants to remember that they’re surrounded by all that nature all the time? Certainly not me. I definitely, absolutely and unequivocally preferred to be intoxicated as soon as the sun went down. Yes, the tarantulas, and scary nights, and bugs, and anacondas were still there, but I didn’t give a shit if I had a few shots of cachaça. And this was how Joachim and Nicklas, the two Swedes, became my friends. We passed the second night drinking at the lodge, downing glass after glass of cachaça and Fanta. Interestingly enough, the cachaça cost a third as much as the soda we mixed it with. It says something about an establishment when their alcohol is cheaper than their water.

The following day, though it began with a rather brutal hangover (more difficult to overcome than usual—it’s hard to stay hydrated in that kind of heat), was off to a solid start. At least we had all gotten some sleep. Nicklas, Joachim, and myself were the only tourists left in our group, and we were treated to a canoe ride through some of the backwaters in the hopes of seeing some of the more elusive animals.

“There,” Joshua said. “Up there. You see sloth?”

The three of us stared at the incomprehensible tangle of branches and leaves.

“No,” I said bluntly.

“O.K. O.K. You wait here.”

Joshua tied the boat to the tree, and before any of us could say anything, he had jumped out of the canoe and began scaling the tree. He had an extremely uncanny ability to climb trees: he seemed more monkey than human in that respect.

“Jesus,” I said, as he disappeared from sight, “he’s like some kind of superhuman.”

“What’s he doing?” Joachim asked, craning his head. “He’s not catching the sloth, is he?”

“No way,” I said. “He wouldn’t.”

“I bet he would,” Niklas countered.

As we debated the matter, we heard Joshua talking—presumably to the sloth—in the trees above our heads. “Come here, baby, come here,” I heard him murmur in Portuguese. The next thing we knew, we saw Joshua lowering the sloth—which he had tied to some kind of cloth harness—down towards the canoe, as Joshua climbed back down the tree.

“Oh my god,” I said. “He didn’t.”

But he had. The sloth was actually kind of cute, if you could look past its enormous claws. Or get over the fact that our guide had just captured an innocent animal that, according to Joshua, was “very, very an

gry.” To me, the sloth looked completely expressionless; kind of like a teddy bear. It made some kind of brief, low noise. “Sloth very angry,” Joshua said cheerfully, poking it in the head, “very angry.”

“Of course it’s angry,” Niklas whispered. “We’re … we’re violating it!”

The three of us were torn between guilt and an incredible photo opportunity. We settled for photos of us guiltily holding the sloth, all three of us taking turns holding it up by the harness, each with a pained expression on our face.

“The title of this Facebook album is going to be ‘the violation of the sloth,’” I whispered to Nicklas and Joachim.

“Poor thing’s never going to get over it,” Joachim said. “Do you think sloths can have post-traumatic stress disorder?”

“How would you tell?” Nicklas asked. “Would it move an entire inch, instead of the fraction of the inch it moved when it was really pissed just now?”

“It’s going to take it weeks to get back up in that tree, at the rate it’s going now,” Joachim said. We all stared at the sloth, completely immobile; it hadn’t even moved its paw from where Joshua had left it on the tree.

“O.K. O.K.!” Joshua said, completely unperturbed by remorse, “I go catch baby monkey now.”

“No!” the three of us shouted, almost simultaneously. “Joshua, no baby monkey,” I protested. “That’s just too close to human for me.”

Joshua shrugged. “O.K. O.K. We go to bar now.”

The “bar,” it turned out, was a shack on the river that sold alcohol. Joshua drank what had to be the equivalent of six or seven shots of vodka, straight up. The man had a tolerance. Meanwhile, the bartender tried to speak to me, but I had trouble understanding his Portuguese. Joshua interceded, his voice slightly slurred.

“He’s trying to tell you,” Joshua told me in Spanish, “that there was another blonde girl here a few weeks ago. She died, though.”

“Oh,” I said, trying to decide if I wanted any further details. I decided that I didn’t.

“What’s he saying?” Niklas asked me.

“Don’t worry about it,” I said hastily.

The bartender went on to explain, via Joshua’s translation, that most tourists don’t visit this particular bar. “Too hard to find,” he said. “Most tour guides get lost in the tributaries around here and can’t find their way back.”

“Joshua,” I said, “do you know how to get back?”

“Why you worry? This girl always worry,” he told the bartender, taking another swig of vodka.

I continued to worry, twenty minutes later, as a little bit of rain turned into a torrential downpour. I could barely see a few feet in front of my face because of the rain. I huddled on the floor of the canoe, terrified of the lightning that seemed to be directly over our heads. I had very little faith in Joshua’s abilities to find his way back to the lodge when he was completely drunk, with poor visibility and a quickly darkening sky on top of it.

“Are you O.K.?” Joachim asked from a few feet above me, as I quaked on the floor of the canoe.

“I’m fantastic,” I muttered, my voice muffled by the fact that I was hiding my face in my hands, silently uttering Hail Marys and wishing I had left more details about my whereabouts with my family. “Tell me when it’s over.”

Much to my disbelief, Joshua did manage to find his way back to the lodge, and the Swedes and I retreated to another night of cachaça and Fanta.

“O.K.,” Joshua said the next morning. “Today we go camping in jungle. This group small, so new people will join tour.” He gestured toward the four Russians who had arrived at the lodge the day before. The Russians, it seemed, had an aversion to both sobriety and clothing. I had yet to see any of them sober (in fact, right now they were pouring vodka into their orange juice with breakfast), and as far as I could tell, the only clothing they had brought with them were Speedo swimsuits.

They did seem to be having an inordinate amount of fun on their Amazon tour, though. They continued drinking and smoking pot throughout the day, as we visited a banana plantation and took off on a boat for our campsite. Our departure was delayed slightly when one of the Russians, completely inebriated, accidentally jumped from the dock and landed in the river instead of in the boat. Joshua and the other tour guide who had joined our group fished him out without incident, while the other three laughed and poured him more vodka.

To their credit, the Russians were incredibly pleasant to be around. Loud, drunk, and barely clothed, they were endlessly entertaining. The Swedes and I declined their offers of alcohol and pot (“Katy,” one of them told me, in a thick accent, “If you like, you can smoke”) and amused ourselves by watching them. The Swedes and I were covered from head to foot in long-sleeved shirts and long pants as protection against the mosquitoes and venomous insects. The Russians had no such concerns; while the Swedes and I sat gingerly on tree trunks, carefully searching them for poisonous spiders first, all four Russians passed out on the ground, wearing nothing but their Speedos. At one point, one of them disappeared into the jungle for a bathroom break; after twenty minutes, we realized that he had truly disappeared. Our guides had to do a full-on search before they returned with him another twenty minutes later, warning him against wandering off and falling asleep when in a dangerous jungle.

Maybe it was passing such a pleasant evening with the Swedes, watching the Russians stumble around the jungle, that gave me a false sense of confidence and made me believe that I was enjoying myself. I was enjoying good company, true. I was not enjoying the monstrously sized mosquitoes, or sleeping in a hammock with no protection from whatever roamed the jungle at night, or the fear that I would be strangled by an anaconda every time I slipped off into the wilderness to pee. I was also vaguely aware that staying that last day after the Swedes’ departure might appear to be a bad idea to some people (namely, my parents, close friends, and anyone who with a scrap of common sense). I would, after all, be the only woman in the lodge. On the other hand, my pride prevented me from leaving early, and I had already paid for my last day at the lodge. Besides, I had reluctantly decided that it was pretty peaceful hanging out on the river.

And that was how I ended up on Day 5 of the Survivor Tour. The last day, it turned out, wasn’t anything particularly exciting or dangerous: my guides gave me the options of going alligator or wild boar hunting, but I declined in favor of going on another canoe ride with the new tour group. My new group consisted of John, an american graduate student, and a German-American man named Magnus who had lived in San Diego for fifty years but had the strongest German accent I’ve ever heard. This canoe ride was much less uneventful; our guide was a man named Michael who wore a camouflage T-shirt emblazoned with the words “Soldier For Jesus” on it. Michael didn’t seem inclined to catch any sloths or baby monkeys, much to my relief. We did, however, visit a beautiful jungle lodge about an hour down the river.

“If you ever come back to the Amazon,” Michael said, “You should stay here.”

Then we paused for a few minutes to appreciate the beauty of the competition. I took an extra moment to appreciate the irony of a jungle tour company that flat-out acknowledges their complete lack of repeat business, and goes as far as to make recommendations for future trips.

That night, we went to a different location for the campsite. “Katy’s already seen the other campsite,” Michael explained. As if there was something to see at the campsites—once our guides had cleared an area in the dense forest, it was like being surrounded by walls of foliage. Again, not very eco-friendly, what with the deforestation and all, but perhaps this was why they didn’t anticipate any repeat visits.

I have to admit, though, that I was feeling pretty bad-ass, being the only person in the tour who had ever camped in the Amazon before. Sure, there were only three of us, and sure, it had only been once the night before, but I was the veteran of the group, and I savored my authority. Or I did until our boat landed, and I was expected to help build our shelter for the eve

ning. I thought wistfully of the Swedes, who had done all the work the previous day (the Russians had swung around on the branches like monkeys, and although they seemed to interpret this as helpful, the Swedes still did all the work). We built a rough frame to hang the hammocks on, which seemed to be a rather precarious sleeping arrangement, but Michael assured me that it would be fine.

“We can swim by the waterfall,” he suggested as I wiped the sweat off my brow.

“I don’t have a swimsuit.”

“We just go with no clothes, then.”

“When hell freezes over.”

Magnus, meanwhile, was not very happy about the camping arrangements.

“Vhat the hell is this?” he said in disgust, his German accent sounding angrier than usual as he stared at the hammock arrangements. “I did not pay to sleep like crap in this … hovel.”

When Michael began protesting, Magnus held up his hand and shook his head. “Don’t vorry, don’t vorry. I vill just take some Valium.”

Michael turned out to be a much more considerate tour guide than Joshua; for starters, he carved us all wooden spoons to eat our dinner with. “Let me see yours?” John said.

“Hey Michael,” John said, “how come my spoon isn’t carved with ‘Marry me my love?’”

“Shut up,” I muttered, snatching my spoon back and glaring at Michael. Michael, undeterred, pulled out his guitar (or some kind of similar instrument) and began singing love songs.

“I think you’re being serenaded,” John whispered, standing up. As he stood, he smacked the back of his head against one of the logs jutting out from the hammock structure. “Vatch it!” Magnus shouted. “I am trying to rest. Vhat is so hard to understand about that?”

Michael ignored him and began singing a creation story, which talked about the world beginning in the jungle and people spreading across the world from the Amazon. It was a beautiful song, and I closed my eyes to listen to it.

Leave the Lipstick, Take the Iguana

Leave the Lipstick, Take the Iguana